Reverse engineering - No. 1

Introduction

In IT, it can be very useful to see behind the scenes. For example, when a company is attacked with a malicious software, on the blue team side we want to understand the enemy’s techniques, tactics, and procedures to effectively defend ourselves. In this case, we need to break down the mentioned program. On the other hand, sometimes we are on the red team, driven by completely noble intentions and with permission, trying to find a flaw in a program so we can exploit it to achieve our goals.

The importance of the skills that can be learned through program reverse engineering cannot be overstated in IT. Cybersecurity is undoubtedly a field where this is especially true. It’s no coincidence that American three-letter agencies invest billions of dollars into this sector.

In this short article series, I will reverse engineer a few “crackmes” using the simplest tools possible. The programs are from the crackmes.one site, where people can upload programs for educational purposes, and others can crack them for practice.

Foundation

Why is that, it’s so incredibly difficult to reverse engineer programs? There are several economic models for software development in the world, but we usually say that a program is either closed or open source.

Closed source, proprietary programs are usually funded and developed by companies, and then the final product is sold. The source code is not published because that would make the program free.

In contrast, open source programs, like the Linux kernel, are maintained by the community, are free, and anyone can contribute and commit to them.

I won’t delve into this debate now, both sides have their arguments, pros and cons, but I will say that from a security perspective, open source projects are in a better position than the other side. The reason is simple, closed source code cannot be verified without reverse engineering. The whole system works on the “trust me bro” principle, as the user has no power to see what the program actually does. This is problematic because it means trusting that the developers have done a perfect job and that the program doesn’t do anything beyond what it claims. We’ve seen what happens when this trust is misplaced (e.g., Facebook lawsuit).

So now we will deal with programs written in C/C++ where the source code is not provided, only an executable file. This executable consists of machine code because the human-readable code is translated by the compiler into the computer’s language. Unless we explicitly tell the compiler to keep the symbols, this translation will be irreversible, code-wise. In short, we won’t be able to read the source code. However, there are advanced “decompilers” like Ghidra that can roughly guess what was the original source code, but we probably won’t need those now.

I will solve relatively simple and beginner tasks, but to fully understand the solutions, knowledge of C/C++ and Intel x86-64 assembly is essential and recommended.

I will use the following CLI programs:

- objdump - allows us to read the assembly code of the program

- ltrace and strace - trace dynamic library calls during the program’s execution (e.g., printf or strcmp)

- gdb - a Swiss army knife for every programmer, a debugger software, but also great tool for reverse engineering

- strings - a simple tool that prints all printable characters found in the file

An important precaution before we dive in: it’s advisable to do these crackmes on a virtual machine since we are about to run an unknown program, even though the exes are checked after upload by the crackme moderators. The virtual environment separates this program from our real system, making it safer. However, keep in mind that even this is not completely foolproof, as if there is, for example, a shared folder in the virtual machine, there is already a bridge between the two systems. Also, there are known malwares that can escape the virtual machine under certain conditions. Nonetheless, none of these probably threaten us, but this precaution and this “adversary mindset”—preparing for the worst—is a useful routine when working in cybersecurity.

Reverse Engineering

For the virtual machine, I use VirtualBox with a bare-bones Arch Linux and the listed tools.

First:

D4RKFL0W’s Easy_firstCrackme-by-D4RK_FL0W

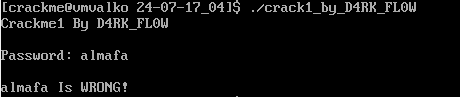

Download it and run it just to see what we’re dealing with.

As you can see, we need to guess or bypass a password, and the password is not “almafa” :(.

Let’s try our tools on it:

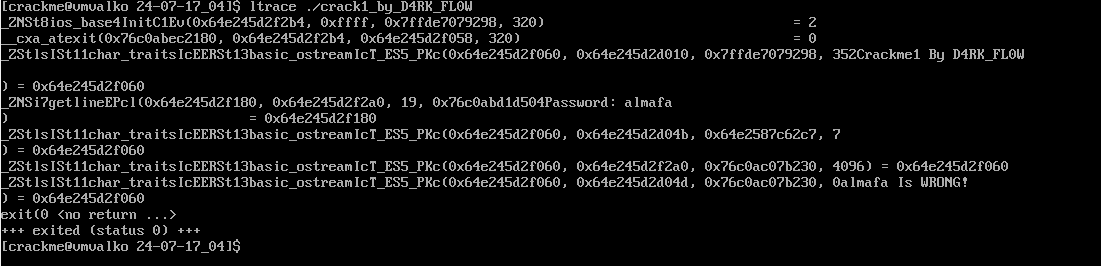

First, let’s look at ltrace. Not much luck here, nothing interesting shows up, just the process of printing out to stdcout. If, for example, the program used strcmp() to check the password, we would have seen it here.

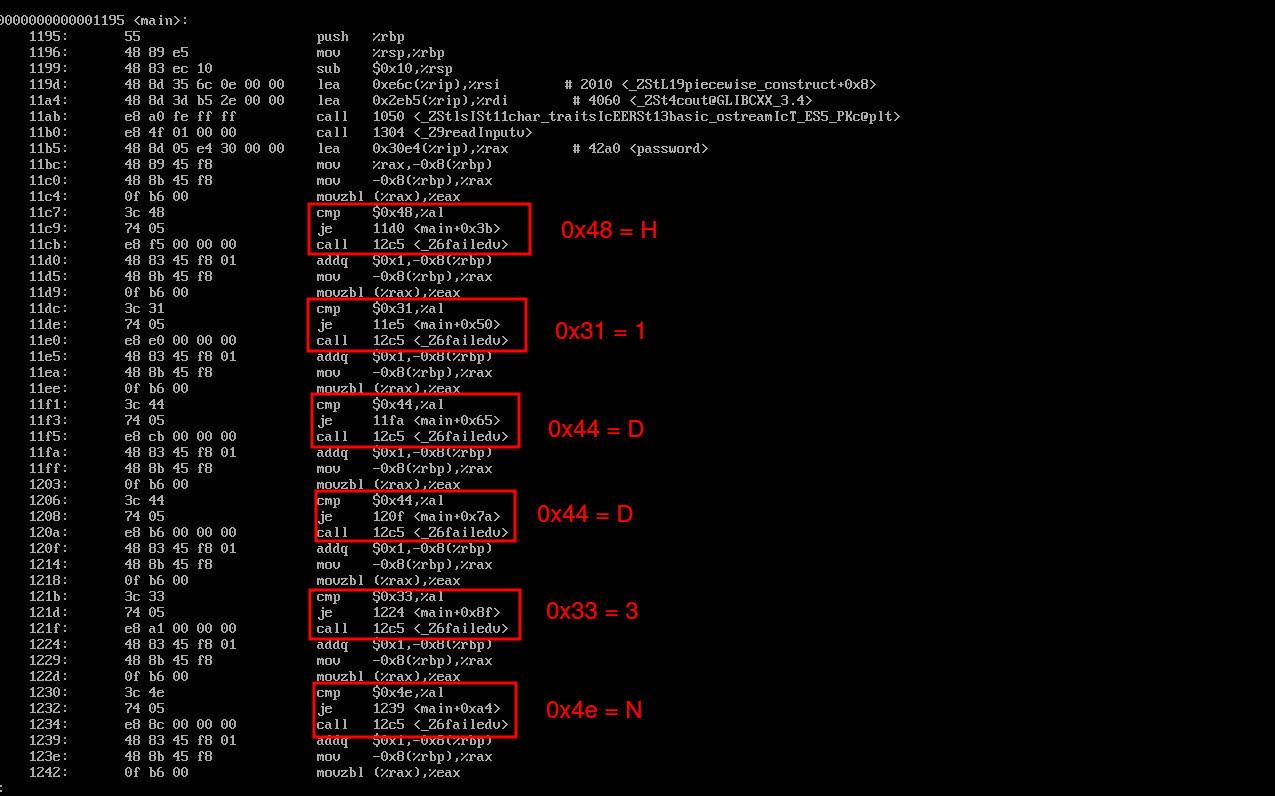

Objdump proved to be much more useful. We look for the main block since the password check likely happens there. Here we see a small pattern that I’ve highlighted. The program checks the entered password character by character with the cmp operator. The “je” instruction corresponds to “jump if equal.” So if the character is equal in cmp to the given hexadecimal value, the program skips the call that calls some “failed” method. Translating the hexadecimal values used in the comparison to ASCII characters and concatenating them gives us the desired password: H1DD3N. Yay!

I should note that it’s never a good idea to check a password character by character anywhere. If it’s necessary, ensure that the check is of constant time; otherwise, the program will be vulnerable to side-channel attacks. For example, if there is a 4-digit PIN terminal that immediately returns “Wrong password!” after entering the first digit, brute force will only require 40 attempts instead of 10,000.

Second:

D4RKFL0W’s crackme2-be-D4RK_FL0W

This one doesn’t seem much harder at first glance; we need to figure out a password here as well.

Strings, ltrace, strace are not very useful here either. Looking at objdump, I didn’t find anything that led to a trivial solution, but I saw a block in the program called _Z14check_passwordPc, which might be interesting for us. However, it was not possible to read the password from the assembly code passively like before, likely because the game maker deliberately designed it so that the program concatenates the password character by character in some hidden part using strcat() or something like that, at runtime.

So we need to step through the program while it runs. I will use gdb for this. Gdb is a bit bare-bones on its own, so I recommend tuning it with GEF to make it easier to crack your neighbor’s Wi-Fi (just kidding).

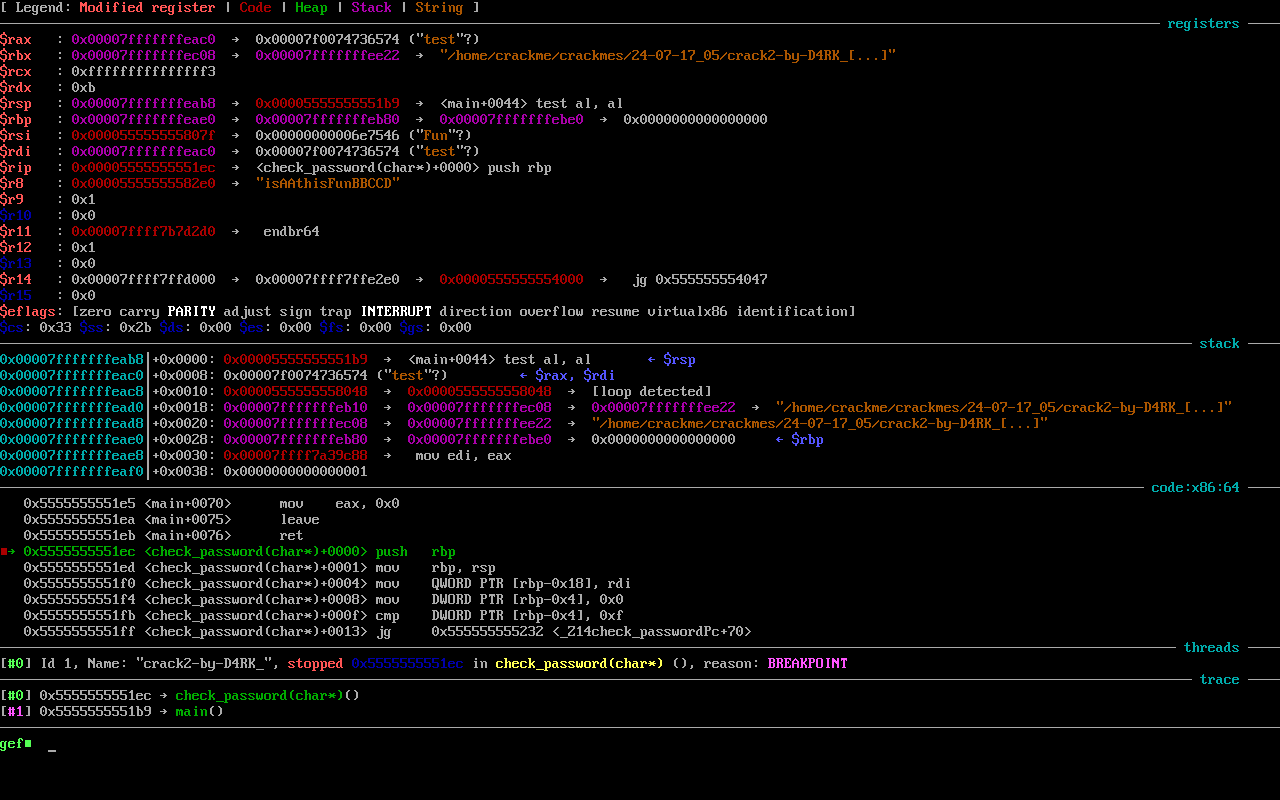

So what I did here:

gbd -q crackme2-be-D4RK_FL0W

Start gdb.

set disassembly-flavor Intel

break *_Z14check_passwordPc

run

I don’t remember what the default disassembly-flavor is, but I prefer the Intel syntax, so I set it to that. Then I placed a breakpoint at the mentioned function to stop the program’s execution there so we can examine it more closely. The run command starts the program.

This is the interface that greets us. To sum up, what we can see:

- At the top are all 16 64-bit registers the computer works with (actually, the computer works with many more registers to execute as much parallelization as possible, but the architecture instruction set is designed for 16 registers, and deviating from this would break backward compatibility, meaning old programs wouldn’t work, so the processor internally maps these 16 registers to its many, probably thousands, of available registers).

- Below that is the stack

- And below that are the assembly instructions, with the next instruction highlighted in green

The rest is not so interesting for us now.

The r8 register looks promicing: “isAAthisFunBBCCD”. We potentially have our winner, but let’s investigate further. When dealing with something like this, if something is too good to be true, it probably is. I say this because these tasks often include “honeypots,” which are easily obtainable bait to mislead people. There is practical use for this in real life scenarios, where honeypots are placed to waste the attacker’s resources and time. Sometimes they even act as alerts, notifying defenders when someone starts attacking the honeypot, giving them more time to prepare for defense.

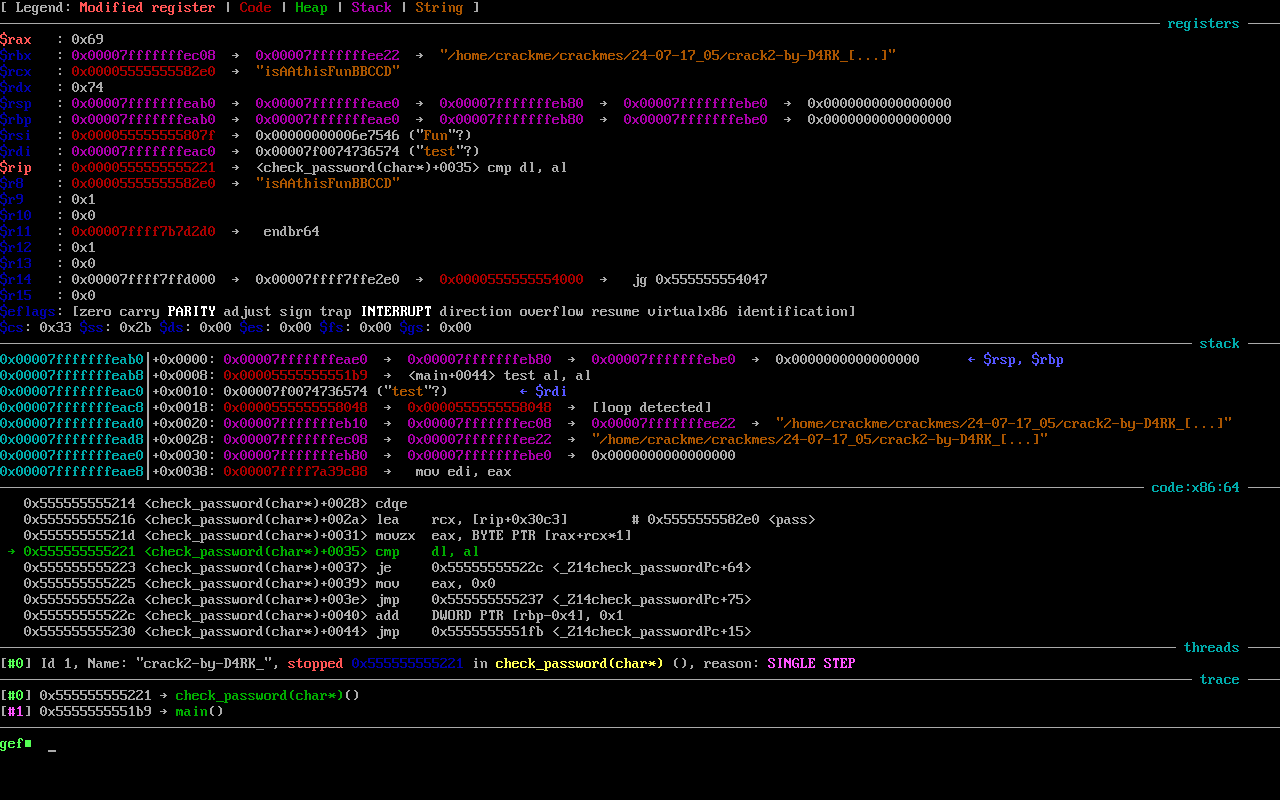

Back to the task, let’s step through the program using the stepi and nexti commands in gdb. The former steps into method calls, while the latter skips them.

As you can see it here, our guess about the solution, is correct since during the execution of the program…

- the rax register will be equal to 0x69(“i”)

- the rdx register will be equal to 0x74(“t”)

- then these will be compared with the cmp dl, al instruction

Therefore character by character comparison is happening here too, where my given password “test” is checked against the “isAAthisFunBBCCD” password. That’s the solution."

That was is for this small introduction to binary exploitation and reverse engineering. If assembly looks a bit scary at first glance, don’t worry you are not alone, but with time and practice you can master it, just like everything else, and I can assure you that it’s going to worth it, especially when you are into reverse engineering.