Locality-Aware programming

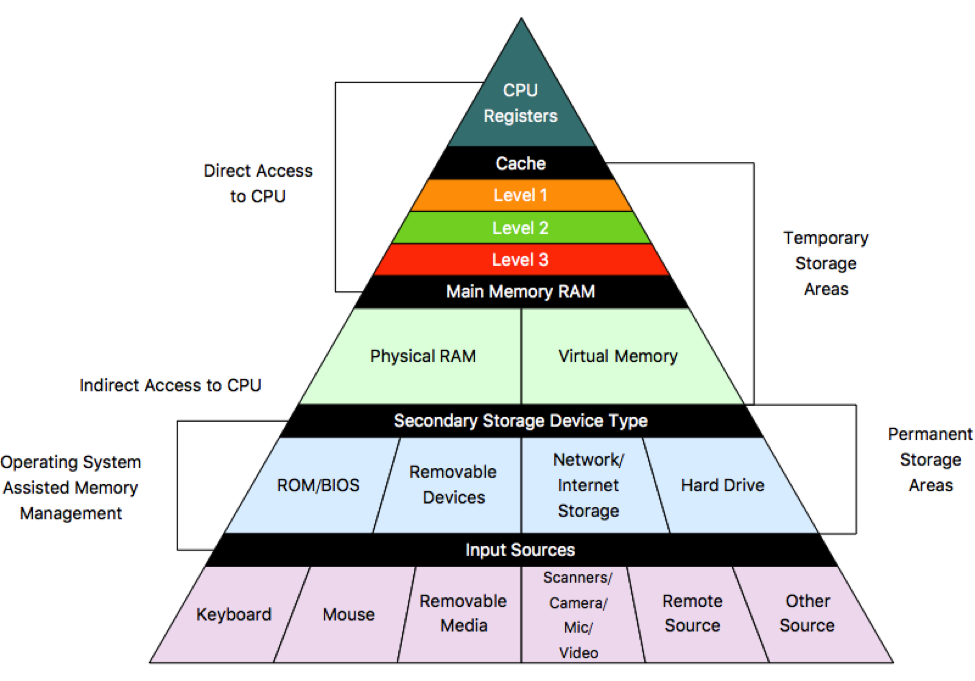

Since the Neumann architecture, during the operation of a computer, the instructions and the contents of the addresses referenced by these instructions are stored in memory. The data used in the program can be accessed from so-called data memory, which is organized into a memory hierarchy.

Memory Hierarchy

A computer’s performance essentially consists of the clock speed of the processor and the memory, with memory often lagging behind the processor. This means that despite having a high CPU clock speed, if the memory acts as a bottleneck, the processor has to wait for the data it needs, leading to suboptimal performance.

Principles of Locality

Fortunately, most computer programs follow certain patterns when accessing memory, known as principles of locality, which we can exploit to improve performance. There are several principles of locality:

If we perform an operation on a data item in memory

- Temporal Locality: …, we will likely use it again soon. Example: incrementing a loop counter in each iteration.

- Spatial Locality:…, we are likely to use the items nearby as well. Example: traversing an array.

- Algorithmic Locality: Programs often work with dynamic data structures like binary trees or linked lists which do not fit into spatial or temporal locality but still exhibit predictable behaviors that can be exploited.

By placing frequently used data and their surroundings close to the processor, we can reduce the number of slow and expensive memory operations. We still store our data in a memory but in a much faster but smaller and higher consumption memory known as cache memory. But what technology is used for cache?

We know several memory technologies, such as the high-density but slower and cheaper DRAM, and the low-density but faster and more expensive SRAM. To stor 1 bit, DRAM uses one transistor, while SRAM uses six, explaining the differences in power consumption, density, and cost. It is impossible to achieve cheap, fast, and large memory simultaneously, so compromises are inevitable. This leads to the concept of memory hierarchy, where the memory is structured in multiple levels, with the most frequently used memory being faster and smaller.

The slowest storage, the HDD or SSD, holds the least frequently used but large amounts of data. Frequently used data are stored in the random-access memory, usually DRAM, and the data used by the currently running program or process (e.g., a local variable) is stored in the cache, made of SRAM.

I will not go into the subtle details of how a cache works here, however if you are interested, it worths looking into how prefetching works, because that’s how the computer loads data into the cache before it’s used, after making an educated guess.

To ensure efficient processor utilization, the programmer should aid the memory hierarchy:

- If the programmer references memory randomly in the cache, many cache misses occur, forcing the computer to resort to the slow main memory.

- In DRAM-based system memory, accessing cells in the same row is fast, but random access to different rows incurs expensive and slow operations, due to the time cost of opening new rows.

The programmer’s goal is to address memory in a way that aligns with the principles of locality. How?

Locality-Friendly Loop Organization

In practice, we often need to traverse one- or multidimensional arrays, requiring loops. I will show you examples of loop organization techniques that utilize our memory hierarchy knowledge to improve our program’s runtime.

Merging loops

Original code:

for (int i=0; i < N; i++)

b[i] = c * a[i] - x;

sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i < N; i++)

sum += b[i];

for( int i=0; i < N; i++)

d[i] = a[i] + b[i];

The above is a simple C code example. Now, let’s calculate the cache miss ratio, which will tell how often do we need to access the slow memory because the data is not in the cache. Let’s assume the following for simplicity:

- N is arbitrarily large

- The cache block size is 64 bytes

- Array elements are 8-byte doubles

- Accessing i, c, x, and sum does not involve memory access.

The first for loop traverses arrays a and b. At i=0, there is a cache miss for a[0] and b[0], as the cache is initially empty. A cache miss loads 8 array elements into the cache, so there will be a cache miss every 8 steps, leading to 2N/8 cache misses for 2N memory references.

In the second for loop, if N is large enough, the beginning of array b is no longer in the cache, so there will be a cache miss every 8 steps again, resulting in N/8 cache misses.

Similarly, the third loop will have 3N/8 cache misses for 3N memory references.

Summing the cache misses, we get 6N memory references with a 12.5% cache miss ratio.

Now, using loop merging:

sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i<N; i++){

b[i] = c * a[i] + x;

sum += b[i];

d[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

This algorithm has the same functionality as the original but is more efficient. The first two memory references in the loop body still cause cache misses every 8 steps, but subsequent accesses to a[i] and b[i] will not cause cache misses as they are already in the cache. The third line will only cause a cache miss for d[i] every 8 steps.

Thus, we have 3N/8 cache misses, reducing the cache miss ratio to 6.25%, half of the original.

The first rule of thumb is to merge loops wherever we can.

Loop Order Optimization

Consider the following example where the order of loops in traversing a 2D array affects performance.

First, the optimal example:

Row-major traversal:

for (int i=0; i<N; i++)

for(int j=0; j<N; j++)

sum += a[i][j];

Before analyzing cache misses, it’s important to note that C stores 2D arrays in row-major order. Thus, a 2D array {{4, 2}, {0, 6}} is stored in memory as

… 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 …

Row-major traversal aligns with spatial locality, leading to a cache miss ratio of 1/8, which can be further improved with prefetching.

Now, let’s see how NOT to do it:

Column-major traversal:

for (int j=0; j<N; j++)

for(int i=0; i<N; i++)

sum += a[i][j];

Here, the loop order is reversed. This time we do not utilize spatial locality, where elements in the same row like a[i][j+1], a[i][j+2], a[i][j+3] are loaded into the cache because, if N > 8, then a[i+1][j], the next reference in our loop, will definitely not be in our cache. If N*8 exceeds the cache size, the situation is even worse, because when the outer loop jumps from j to j+1, until then a[i][j+1] will be long gone from the cache, since other array elements pushed it out from there. This results in a 100% cache miss ratio.

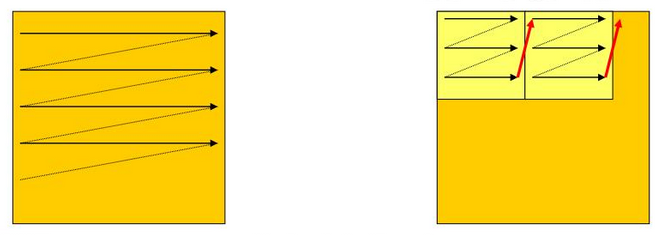

Traversal with blocks

Another technique is the so called loop tiling, where a matrix is traversed in blocks. This is useful for operations like transposing a matrix:

for (int i=0; i<N; i++)

for(int j=0; j<N; j++)

b[j][i] = a[i][j];

Here, a is traversed row-major, and b column-major, resulting in a 100% cache miss ratio for b for large N, as you can see the reasoning in the paragraph above. We can improve this with loop tiling:

for (bi=0; bi<=N-BLK; bi+=BLK)

for (bj=0; bj<=N-BLK; bj+=BLK)

for (i=bi; i<bi+BLK; i++)

for (j=bj; j<bj+BLK; j++)

b[j][i] = a[i][j];

This may seem obfuscated, but here is a diagram to help:

Choosing an appropriate block size (BLK) is crucial, as the goal is to minimize the total number of cache misses.

Though matrix transposition may seem as an edge case scenario, matrix operations are actually very often used, such as in GPUs which is optimized for these tasks using more advanced techniques.

Summary

We have explored an important aspect of our computer, the memory hierarchy, specifically focusing on the cache. Using this knowledge, we have found solutions to practical problems that result in better performance. What more one could wish for? :D